WORDS BY DANIELLE KHAN DA SILVA, IMAGES BY ALEX MOANA KING

“Tell us a story, Papa Mike.”

As the children gather round the fire, Maōri Elder Michael Teatuakaro Tavioni (age 74), tenderly known as “Papa Mike,” begins to tell a tale.

“A long time ago, our ancestors lived in another place where the daylight hours were shorter. They realized that with longer daylight hours they could work the land longer, and produce more food for the community. So Maui, a demi-god ancestor, decided to use his grandmother’s jaw as a fish hook, and her hair as a net, and cast a line towards the sun, pulling it closer, and making our days longer.”

He chuckles. “Of course this is a lie. But if I told you the truth it wouldn’t be as interesting. This is the root of our mythologies—they are stories that help us remember our history; that our people decided to voyage across the ocean to find home here where we have longer daylight hours. That is the meaning of Maōri—‘Ma’ meaning ‘pure people’ and ‘ōri’ meaning ‘voyagers.’”

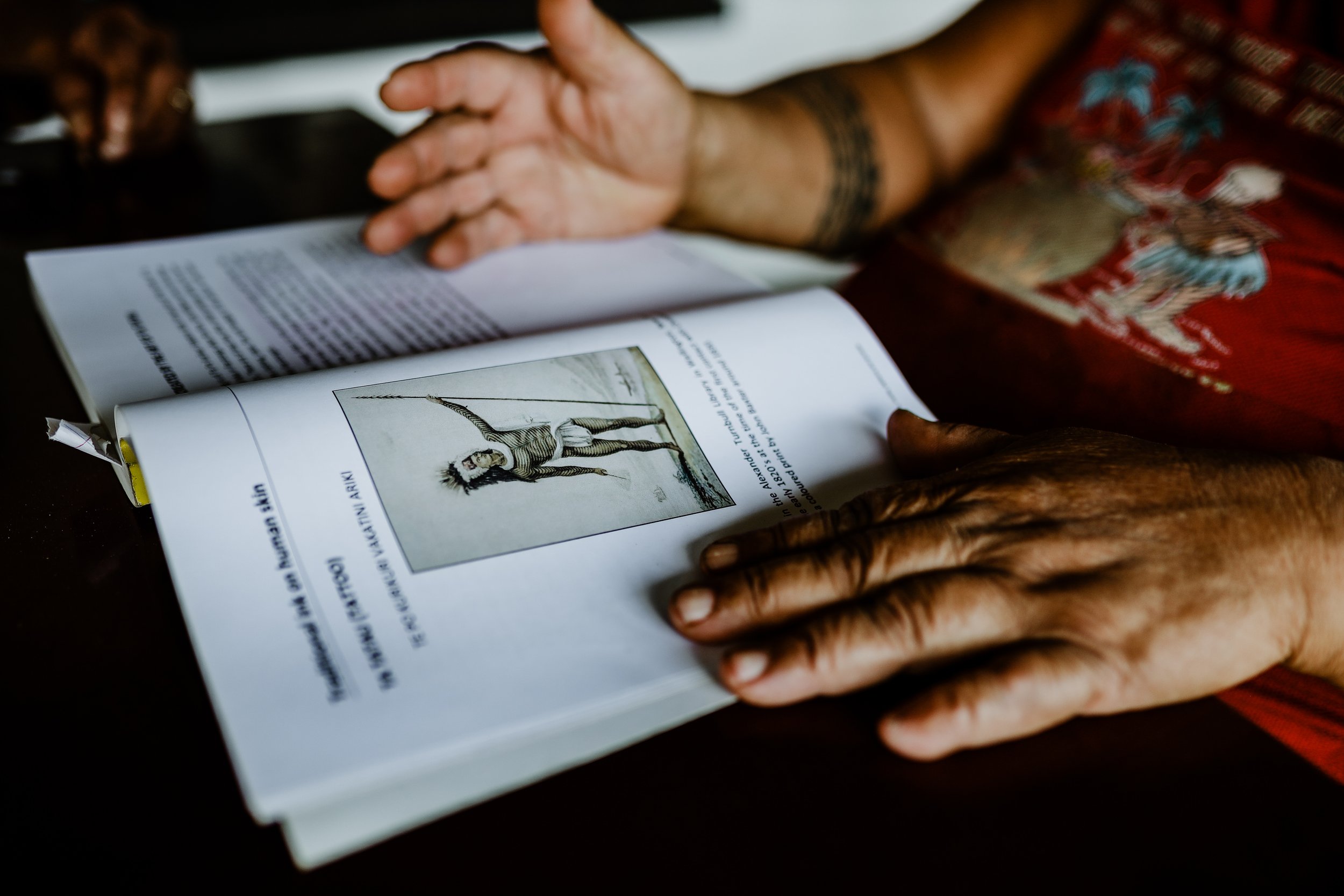

Ta’unga korero (the keeper of knowledge) Papa Mike is a ta’unga (expert)—someone who has the ability to ‘see’ or perceive what others can not.

Papa Mike and his partner, who is known affectionately as “Mama Awhitia,” have been on a mission to pass down Te Reo Maōri (language), traditional knowledge and the inherited skills from their ancestors around building traditional fishing vaka (canoe), relaying genealogy, and understanding cultural artefacts on the tiny island of Rarotonga in the so-called Cook Islands, which spans only 11 kilometres of land as well as 2 million square kilometres of surrounding ocean.

Papa Mike is a writer on medicinal plants, corrected Polynesian history, poetry, and Indigenous methodologies and mythologies. He is also a traditional carver along with Mama Awhitia and together they run “Gallery Tavioni” and a vananga (traditional school). Both projects have slowly been attracting more attention with their roadside displays of art, and particularly with their most recent project called “Te Mana O Te Vaka” (“the power of the canoe”), a collaboration with the Cook Islands Voyaging Society with the goal of constructing 8-12 traditional canoes (vaka). There is no other cultural education space like this on the island, and there is certainly no other project like this. Most importantly, the pair are bringing community together with their work— something Papa Mike believes has been crucial to the survival of the community since long ago.

For months, members of the community have been gravitating towards the project where giant logs have been hollowed, carved, lashed, varnished, and strapped together. They have even made traditional hand-woven sails, which take days to make. All of these elements emanate “mana” with all the hands that go into them, and it is an emotional process to witness as people of all ages, once disconnected from their culture by colonialism, bring these crafts to life.

Developing the vananga is of utmost importance for Papa Mike and Mama Awhitia as it will benefit the community now and for future generations to come. Tiny island states like Rarotonga are not only more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change with rising temperatures and sea levels, but also to overfishing, illegal fishing, water shortages, drought, over-tourism, waste management, and environmental extraction and exploitation.

“All of these things people think they need…are just luxuries. In reality, we have everything we need here. We have taro, taro leaves, seafood, coconut, water cress and more...There will come a day when we need to know how to live off the land again, and when our traditional practices will be necessary again,” he urges. “During the COVID-19 pandemic it seemed that things got better. With no tourists to accommodate, the prices of food and housing went down, and people were returning to the land for sustenance,” he says.

Now as the island has started opening up, prices have risen as a surge of tourism is once again over-burdening the small island. A head of broccoli, for example, can cost up to $13 USD. Housing is more expensive as already scarce properties are rented to tourists at profitable rates.

According to Papa Mike, the “Cook Islands” were named not by the Indigenous Maōri people who have lived here since time immemorial, but by a Russian mapmaker who named them after the colonizer Captain James Cook (who ironically never stepped foot on any of the islands and ultimately met his demise while landed in Hawaii). Papa Mike rejects the naming altogether, preferring the name “Nukutere,” which means “the people that move.” He also reminds us that the Maōri never claimed land at all; they claimed “the ocean blue” or “Moana Nui Kiva” (which was never referred to as the “Pacific” Ocean by their people—another name enforced by outsiders). Their claims were not and have not been respected to this day.

Following the creation and completion of the vaka will come the launch of the vaka into the Avarua Harbor along with a traditional ceremonial blessing. Papa Mike plans to fundraise to support a fishing competition that will enable the community to put the canoes to use and demonstrate the abilities of the “Cook Island” Maōri people to sustain themselves.

As for the future, Papa Mike and Mama Awhitia are not entirely sure if society will take a turn fast enough to combat the threats that loom over this beautiful paradise, but they are sure that they will spend the rest of their days trying to make it happen, educating as many others as they can along the way. They hope that with the creation of a traditional vananga (a Māori cultural school) that they will be able to carry on sustainable practices such as making vaka and using them for fishing, planting taro, and more.

These images were created by Maōri storyteller Alex Moana King, who is considered as a daughter to Papa Mike and Mama Awhitia and has forged a relationship with them for many years. Alex not only documented the entire process, but also contributed directly to the work involved as well.

This story was created with the support of Aesop and our Revolutionary Storyteller Grant.