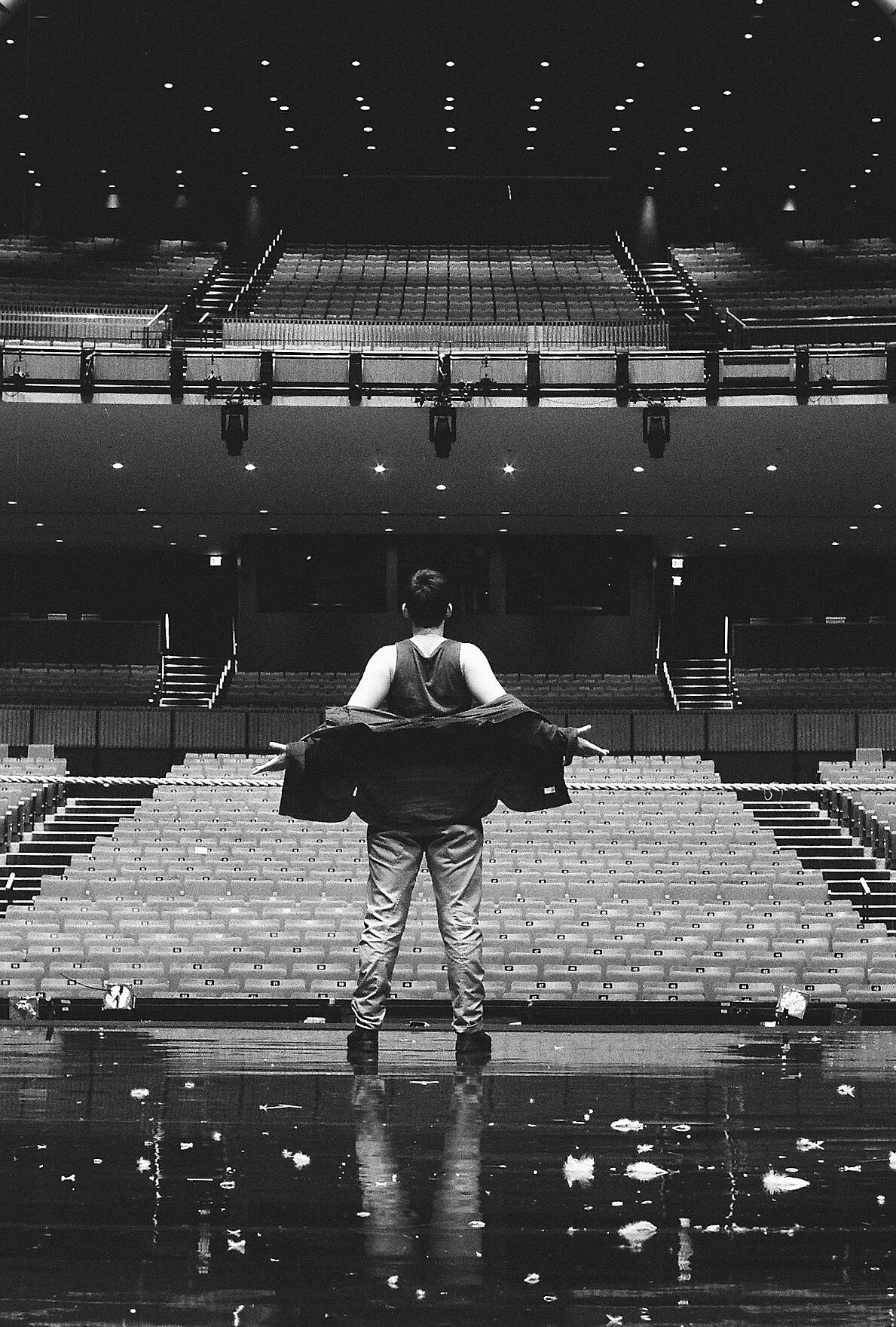

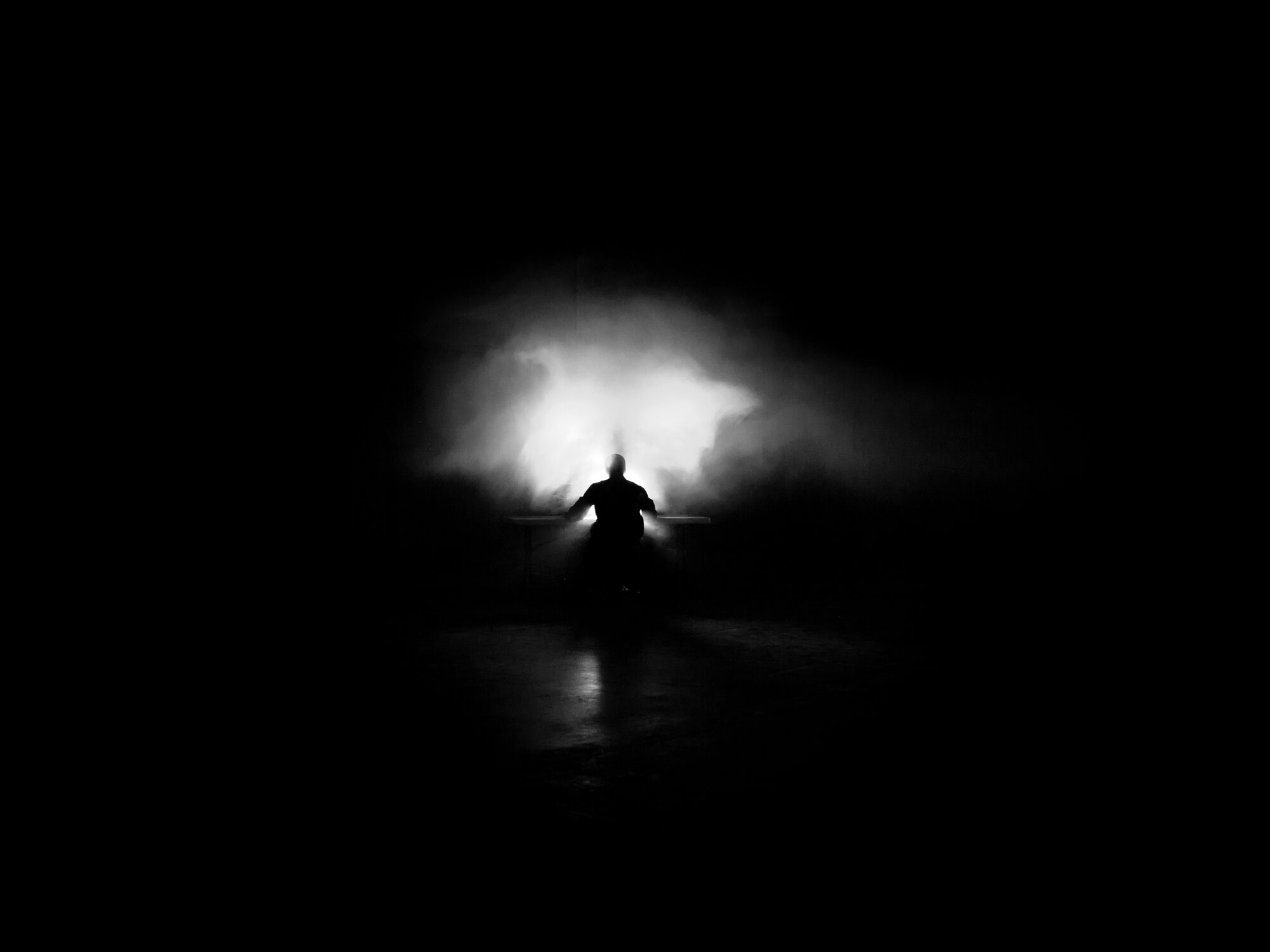

Known online as Aboya.8, Michael is now a fine art and fashion photographer based in Ghana, West Africa. His images explore the emotions, love and strength of humanity through creative uses of composition and lighting.

Known online as Aboya.8, Michael is now a fine art and fashion photographer based in Ghana, West Africa. His images explore the emotions, love and strength of humanity through creative uses of composition and lighting.

Polly Irungu sat with PWB Founder Dani Khan Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series to discuss her work with Black Women Photographers.

Oceans contain more than 97% of the world’s water. Collectively, it's the largest ecosystem on Earth, and the planet’s life support system.

But what are we doing to protect the oceans? What steps are we taking to care for and preserve the marine ecosystems that live in these bodies of water.

Every single one of us has a role to play in ocean conservation.

Photographers Without Borders (PWB) caught up with Meaghan Ogilvie, a Toronto-based photographer and internationally-recognized visual artist whose work raises awareness about water conservation.

Specializing in underwater photography for the past 12 years, Meaghan is known for her unique style that explores what connects us to the ocean and waterways. Her work has been exhibited across North America and Europe and has taken her diving around the world.

PWB Founder Danielle Da Silva sat down with Meaghan to talk about her work and her vision of the world we can all create and live in.

Da Silva: Water constitutes a large portion of our bodies and a large portion of the planet. It’s such a beautiful medium. How did this path happen for you, Meaghan?

Ogilvie: I want to share my first memory of water, which is a bit ironic now that it's such a huge part of my life, career and creativity. But my first memory of water was almost drowning when I was really small. When I think back to that, I don't remember the fear of it. I remember the muted sounds, looking up at the surface and seeing his beautiful light. I felt so weightless. The sensations that I felt is what now translates in my work.

About six years into my photography career, my dad was diagnosed with a rare disease. I wanted to bring awareness to it and use my creativity. So I decided to create a series that would be striking and beautiful. At that time, underwater photography was not as accessible as it is today. But I got friends together, we went to a pool and we learned as we went along. This became the momentum for my career to talk about issues that are important to me. I won a few awards, and it kept me on this path of understanding water on a more spiritual, physical and mental level.

Images by Meaghan Ogilvie

Da Silva: Beautiful, wow. What’s the feeling of being in water for you? How has it changed?

Ogilvie: I suffer from anxiety, like a lot of people do. But when I’m in water, it completely changes who I am. I come out of the water, and my mind is clear and calm. My body feels really good. I believe it’s therapeutic and healing, and that's why I’m so attracted to the sensations of water. I also like the playfulness that comes with it. It’s an adventure every time—you don’t know what you’re going to see and experience. It’s definitely a mental thing with freediving, as well. It helps you to go inward into yourself, believe in yourself and really focus on feeling the sensations when you’re in water.

Da Silva: Can you tell us a bit more about some of the stories behind your images?

Ogilvie: My work has been used as ways to raise money for conservation efforts. Personally, I want people to remember the connection that we have to water. When they see an image, they hopefully can relate to it because it feels familiar. And it becomes something they want to care for and protect.

Images by Meaghan Ogilvie

My work uses a lot of escapism. I didn't do that on purpose; it’s just what I was attracted to and the style that I create. I want to open people's imagination so that they imagine themselves in the place I’ve created. In this case, it can give people the inspiration to go in the ocean or in the water, and to want to feel what that’s like.

Sometimes the nudity in my work is misunderstood as being sexual or a certain type of sensuality. But, for me, it's more about stripping away the layers of society—labels and everything—and being in your natural state. It's a raw moment reconnecting with something that is so beautiful and natural. It's also trying to portray that feeling of being in water and having it touch your skin. It’s simplifying the experience to its raw form.

Da Silva: I love how you were able to express water without being in water and how it continues to flow with the rest of your work. I’m curious about your method of storytelling. When you’re working with people or executing your own idea, where does your mind go when you’re trying to craft a photoshoot?

Ogilvie: I’m more of an intuitive shooter. I have a concept or an idea in my mind, but I’m not stuck to it. I don’t like too many parameters. Take this image, for example. It was too cold to be underwater. So we chartered a boat looking for locations, and we found this beautiful little rock and really clear water. I was thinking about this image as symbolic of rising sea levels, loss of land and displacement of people.

Images by Meaghan Ogilvie

Da Silva: Do you have any tips for anybody who wants to get into water and potentially start making photographs?

Ogilvie: Just get out there and do it—that’s the way I learned. It’s trial and error. The most important thing is that you’re comfortable in the water.

Da Silva: What do you feel is the antidote to the disconnection we are facing to water?

Ogilvie: I'm seeing it from the perspective of living in a big city. There's this huge disconnect because we see water coming out of our tap or we use it for recreational purposes. It's not about understanding. I believe there's a spiritual level and a healing aspect to water. We need to remember that water is a living thing that sustains us all. It gives us life. That lesson is what the Anishnaabe women really taught me and showed me. In the city, we forget that water is essential and precious—and should be protected.

To watch Meaghan Ogilvie's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Using her talents to spark positive change in the world, Nitashia Johnson is a multimedia artist, an alumna of the Rhode Island School of Design and a winner of the 2019 Sony Alpha Female Creator-in-Residence Award. Her work revolves around educating and inspiring those around her. She is a founder of a creative arts after-school youth program called The Smart Project and the creator of The Self Publication—a photographic book series that shares reflections and images from members of the Black community.

Nitashia recently sat down with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion which touch on mentoring, self-love, working with good energy and how to photograph political actions and be a good BIPOC ally.

Da Silva: You're an artist, a youth leader and are publishing your own magazine. How did you start on your path?

Johnson: I grew up in a project in West Dallas, Texas. It wasn't the best, but we did what we could to get by. As a kid, I didn't always see the negative things happening. I was positive, and thankfully for my grandma and my step-grandpa, I held my head up high. My granddad told me to keep the innocence inside of me, because he noticed that I had a good spirit.

I grew up moving all over the place. I actually flunked the third grade because the year I stayed with my mom, I don't remember being in school the entire year. It was really disruptive. All of that took a toll on my life. But luckily, I did meet a lot of good teachers and mentors who believed in me—and they pushed me to the next level. I can honestly say that if it wasn't for them and the family members I had around me, I wouldn't be becoming the person I am today. So I'm trying to do the same thing that others have done for me.

Images by Nitashia Johnson

Da Silva: I'd like to talk about your work with The Self Publication. Can you tell us a bit about how you decided to start it, and what it is exactly?

Johnson: I would say my life inspired the magazine, but what really inspired it was when I went to grad school. There, I disconnected from friends and family and everything back in Texas. But I started to see harsh memes and stereotypes about the Black community being shared online. Some of those stereotypes impacted a lot of my friends, as well as myself. My friends were worrying about microaggressions at work, problems within their relationships, how they're viewed, how they have to compromise and sometimes change their voices or their stance to get jobs. It's all very draining on the human spirit.

So I wanted to open up a platform for Black people to talk about themselves as a way to allow other people to relate. That's how The Self Publication began. It's hard, because I do it all alone, but I wouldn't change it for the world. I really love my culture, and I love the idea of people reading it and understanding it.

Images by Nitashia Johnson

Da Silva: How do you find the stories for The Self Publication? And what's some of the feedback you get from folks whose stories are included?

Johnson: When I look for participants, it's either by word of mouth or an online post. It's important to me to include people who are very thoughtful, who care about others, who believe in themselves and who are comfortable enough to share their stories. I don't want to force anyone to do anything. I'm all about good energy. I've met over 28 people with good energy, and they're just all for it. After the book is published, they usually say, "Thank you for allowing me to tell my story." But I thank them for wanting to share those stories with me.

To watch Nitashia Johnson's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Laura Wood is a photographer and educator based in South Yorkshire, England. She is a mom to two young boys, with motherhood and daily life inspiring much of her photography, and the co-founder of Phlock Live—a photography community hosting educational webinars and workshops.

Wood finds catharsis through self portraiture by taking feelings and emotions out of head and heart and holding a mirror up to herself by way of the camera. This process has given her a tangible way of dealing with everything from sleep deprivation, depression and anxiety to overwhelming love and gratitude. She is a firm believer that finding our creative voice is simple when we strip away expectation and pressure, and focus solely on instinct, impulse and freedom.

Laura joined Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion, which explore the centrality of motherhood to her work and the beauty of “in-between” moments.

Da Silva: You're one of the only people I've ever seen put “I'm a mum” in the first sentence of their bio. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Wood: I'm very proud to be a mum. So that's part of it. But also, the fact is that I am a mother before everything else in my life.

Images by Laura Wood

Da Silva: There’s this beautiful, nostalgic quality to your photographs and these really real moments that are so creatively photographed. What makes you see stories in this way?

Wood: Something that really interests me is the idea that motherhood—being a parent—is totally timeless. You can look at an image from hundreds and hundreds of years ago and see the same connection between a parent and child as you would even 20, 30 or40 years from now. Nostalgia is about being transported to the past and feeling everything we felt in those moments, and I’ve held that close to me in my work. My images are my way of keeping those feelings and leaving a legacy that shows my children the kind of mother that I was, and the relationships that we had in the life we lived.

Da Silva: Do you photograph other families?

Wood: Yeah, I do. I find that the clients coming to me want to tell their true story. Rather than getting the shots where everybody's smiling and looking at the camera, they want something that tells the story of what makes their family so uniquely beautiful, because every family gets along in a different way.Being able to capture that is such an honor. It’s the in-between moments that tend to pull on my heartstrings the most because they are the pieces of our lives.

Images by Laura Wood

Da Silva: I'm curious about your process. Do you always carry your camera with you? What do you wait or look for?

Wood: Sometimes I’ll take my camera out for a full day, but I don't shoot constantly because my kids need to feel that their mom is present. I'll often get these moments where it strikes me that I'm a mother. And it's just through simple things like seeing my reflection when I'm holding my child or realizing I've not been able to shower that day because the kids have needed me so much. I let those moments of realization feed into the stories that I tell: the story of what I'm feeling in my heart and in my head.

Da Silva: Can you tell us about Phlock Live and how that idea came to be? What it is and who it's for?

Wood: In the beginning, it was about elevating the position of women in the industry. I'm providing opportunities for women to teach, to speak, to learn and to grow in a safe space where they can feel creatively free and nurtured. And then I thought, this is not just for women—this is for marginalized genders, including women, but also for our non-binary and trans friends. The main thing is elevating the position of photographers in the industry, with marginalized genders top of mind in everything we do.

To watch Laura Wood's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Travel photography came to a halt in March 2020, with many photographers finding alternate ways to express creativity and make money during the pandemic. For Erin Sullivan, the world got much smaller.

A travel photographer, outdoor expedition leader and host of the REI mini-series In Our Nature, Erin began to experiment with miniature photography. She crafted grand scenes of outdoor adventure from the confines of her Los Angeles apartment.

The result: a photo series titled 'Our Great Indoors' that went viral on social media.

Brands such as Adobe, Nature Valley, Paul Mitchell and Cathay Pacific have since worked with her to create imagery or craft Instagram campaigns. Erin uses Instagram to not only showcase her work but expound on responsible tourism, ethics in travel photography and overcoming harassment as a female in the largely male-dominated travel photography space.

Recently, Erin joined with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Dani Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion.

Dani Da Silva: Can you talk about the problems that exist in the travel industry that you're particularly concerned about?

Erin Sullivan: Right now, a lot of the world is awakening to systems of racial oppression and injustice that have been around for a long time. And I've been seeing that more specifically in my circles of travel photography and the outdoor industry.

Within the travel industry, you have to think about the power dynamic that exists when there's a camera. Think about phrases like "taking a photo" or "capturing a photo." These words indicate a power structure.

Say that I'm visiting an African country, like Kenya, and I have my camera. I'm walking around a village, and I'm taking photos. If I'm taking a photo of a kid, did I ask their parents for permission? Where are those photos going to end up? Am I perpetuating a negative stereotype? I also have to consider the history of colonization and the history of missionaries in these countries.

There are so many dynamics at play, so many things that storytellers need to consider because we can end up making photos that perpetuate a harmful stereotype. It can be totally unintentional and innocent. But unfortunately, it's not the intent that's going out there. The context is really important, no matter what your intention is.

Images by Erin Sullivan

Da Silva: How does the way you position yourself influence the way you tell stories?

Sullivan: I can't remember the quote exactly, but someone said "When you're used to having all of the power, equality feels like oppression." Certainly, over the years, I've thought, "Am I going to lose jobs because I'm not a woman of colour?" I don't think we need to push those thoughts away. Instead, we need to catch them and think, "Oh, that's a triggering insecurity. Why is that triggering interesting?"

Then, really look at it and figure out why it's uncomfortable. We often don't realize that people of colour haven't had many opportunities until very recently. And the way to move forward is to uplift all voices, especially the ones that haven't had a stake before.

Da Silva: How has this awareness influenced your lens as a storyteller?

Sullivan: Personally, I'm on the road of unlearning and unpacking my privilege. I'm always asking myself how can I really contribute here, and how can I share a story rather than tell a story if it's not mine to tell?

If I'm just inserting myself into a story that's not appropriate for me to be in, then I would rather make a connection that gets the story to the right place or to the right photographer. The biggest way that this plays a role in my personal work is that I end up being more collaborative because I recognize that I'm not right for every job. That's helping me learn so much more and to become a better citizen of the world. I really try to listen more than I speak.

Images by Erin Sullivan

Da Silva: How can we become better travellers and photographers when we're not in our own community?

Sullivan: A way to collaborate is to listen first, and to share other people's work and words. As you do that, you'll make authentic relationships. From authentic relationships comes authentic collaborations that are based on similar values.

Sometimes, the camera can be a good conversation piece. But I would argue that more often than not, it creates a separation because of the power dynamic that we talked about. So becoming a better travel photographer is to have our cameras out less and to form relationships first. So when you do take the camera out, there's a level of trust and comfort—and you have permission from the folks you're photographing.

To watch Erin Sullivan's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Emmy nominated director, award-winning National Geographic photographer and marine conservationist, Andy Mann uses his breathtaking images to help tell the story of our rapidly-changing planet. Andy's imagery is memorable, reminding us how the emotion of an image can touch our spirits.

As part of Photographers Without Borders (PWB) ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series, Andy joined PWB founder Dani Da Silva for a conversation. They discussed Andy’s circuitous journey to becoming a conservation storyteller, taking stunning yet risky photos, his dreams for the world and how music influences his storytelling.

Da Silva: How did your journey into conservation storytelling begin?

Mann: It began growing up in rural Virginia and being on the water every day. My grandfather was a crab fisherman in the Chesapeake Bay. As a kid, I was fascinated with marine life and sharks. It seems there was definitely some seed, or something embedded in me, that drove me this way. I just have a love for the wild.

My journey to being a conservation storyteller has been a long crooked road. I moved to Colorado after I studied fisheries management in college. I then moved back to Virginia and worked in the department of game and fisheries doing fisheries work. I loved it because I was a technician and made eight bucks an hour. But I was on the water every day. I realized if I wanted to be a marine biologist or get a PhD, you don't have the same access. You're usually chained to a desk and in some sort of institution at that point.

I moved to Boulder, Colorado with my college roommates and fell in love with rock climbing, It became this thing that took me and led me to a camera. My goal was to rock climb as much as I could in my 20s, and I'd seen photographers do that on trips. Then I started learning how to use a camera, which led me into the doors of National Geographic adventure expedition—and then into marine conservation.

Da Silva: This is such a beautiful image. What do you think the impact of this image is?

Images by Andy Mann

Mann: I think people initially think, “Oh my God, you were so close to an alligator that didn't want to bite you?” And I think that's great, because that's an element of humanity within the image that someone relates to. They put themselves there for a moment. We need to be able to imagine ourselves living in harmony with wildlife and a healthy planet. We need to envision ourselves there.

Da Silva: It's interesting when we think about the vision that we have for the world. What is your vision of the world?

Mann: In my mind, it's a total dreamscape! We can build a beautiful planet. Some of the biggest buildings in the world now are sustainable, beautiful and in harmony with nature. So my vision for the planet is a place swimming with amazing animals that also has a healthy and vibrant human population.

Image by Andy Mann

Da Silva: What is the most important teaching that you've ever received that you want to share with all of us?

Mann: It's about paying attention to the edges of a story. But the best tidbits I get about being a storyteller come from music. A story is so much like music—a great song strives to be a good story, and a good story strives to be a great song.

To watch Andy Mann’s entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB member. As a member, you’ll have access to all “Storytelling for Change” sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Damari McBride is a Brooklyn-based portrait photographer who shared his experience photographing the complexities and communities behind the poaching epidemic in South Africa on the "Storytelling For Change" webinar series. Below are excerpts from his session, where McBride discusses his work with the non-for-profit organisation Nourish and his experience as a part of Photographers Without Borders documentary "Beyond the Gun."

Danielle Da Silva: Can you tell us about the organisations you worked with during your anti-poaching photography assignment in South Africa?

Damari McBride: Nourish is an organisation that's trying to solve the issue of poaching by solving the issue of poverty.

They believe that education is essential to prevent poaching. We visited one school that Nourish works with in the province of Limpopo, and it was cool to experience what the kids were doing to combat climate change and preserve the environment. They were extremely kind and independent.

Limpopo has a lot of animal reserves where injured wild animals are nursed back to health before being released back into the wild. We went to this snake sanctuary with the school kids. The facilitator asked us, "Who's afraid of snakes?" I raised my hand. They asked me why? I explained that I'm not truly afraid; I just don't understand snakes. The facilitators assured me that by the end of the session, I'd understand them. During that time, I held a baby python and tried not to freak out. But I learned so much about snakes within that hour that when I left, my fears were gone.

Images by Damari McBride

Da Silva: That's a great example of the many activities Nourish does to bring kids in connection with animals in a healthy way. By developing love and compassion through education, kids have alternative options to poaching. I remember some of the Nourish staff said if they weren't working there, they'd likely be poachers.

Damari and I also worked closely with an anti-poaching organisation called Protrack during our time in South Africa. Often when we think of anti-poaching, we think of guns. Vincent Barkas, the founder of Protrack, said that we've been stopping poaching and poachers all wrong. We've got to put our people first instead of putting our animals first. Can you talk about meeting Vincent and what you took away from talking with him?

McBride: I took away the fact they're hiring local people for the anti-poaching unit in order to give them a fighting chance at creating money, because that's why poaching happens. If I need money, I'm looking how to get it. In this case, poaching sounds like a good option. Poachers are basically hiring Black folks to work for a big payoff, which ultimately benefits those higher in the wildlife trade food chain.

Poachers are actively exploiting the deep poverty of Black Africans in the area. And poaching isn't easy. People are taking a massive gamble by going into the park at night to attempt to find a rhino, kill it, take its horn and make it out alive. It's incredibly dangerous. For example, elephants tend to be extremely aggressive at night and will attack people. So poachers are risking a lot, but they have to choose between not providing for their family, or meeting their needs for a certain amount of time. It's hard to realise that the choice of poaching comes down to people wanting to survive or saving the wildlife. It's like they're thinking, “While I admire and want to save wildlife, providing for my family is more important for me than the animals.” It's a complicated situation.

Image by Damari McBride

Da Silva: It's so complex, right? Apartheid created game reserves for white hunters and wealthy—often white people—to come and see the animals. But it was often at the cost of the local Black communities' lands. Apartheid, colonialism and segregation all had impacts on separating the people who took care of the land from the wildlife. It created economic disparity, which leads people to take the risk of poaching. One rhino horn can pay up to one million Rand, which is more than someone can make in a year from farming.

McBride: Yeah, the median income for a Black farming family is about 5,000 Rand a month, or just over $400 Canadian dollars.

Image by Damari McBride

Da Silva: How did you feel after the project was finished? How do you hope that your images and your storytelling will make an impact going forward?

McBride: The project made me more aware of social issues and speaking out about inequality. I used to be extremely shy about that. But it's challenged me to challenge people to ask the hard questions and, if they feel something is wrong, to speak up about it. The trip made me appreciate our environment and our planet more. For my work, I'm hoping that it will help people begin to think about issues around inequality and identity.

To watch Damari McBride's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Image by Ian Morton

Rosem Morton is a Filipina photographer and nurse based in Baltimore, Maryland. As a National Geographic Explorer and a We Women artist, she produces visual stories that focus on human relationships and resilience in areas of trauma recovery, culture preservation and health outcomes. She is also a contributor for NPR, The Washington Post, Reuters, The New York Times and CNN.

As part of the Photographers Without Borders (PWB) ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series, Rosem joined PWB Founder Danielle Da Silva to discuss the unique experience as a nurse and photojournalist during the time of COVID-19, the importance of staying safe and following the safety measures that are currently in place, ethics, and the power of storytelling.

Da Silva: You're in a unique position at this time to be both a nurse and a photojournalist. I'm curious what's that looking like for you, especially now during COVID-19?

Morton: Being a nurse during COVID-19 has given me a lot of good perspective, especially in safety, what kind of stories are important, and what kind of stories are getting left behind and need to be told. It's an interesting time, but it's also really emotionally tiring.

Da Silva: You posted a Washington Post article on April 3rd, 2020. It was entitled: Americans want to see what's happening in hospitals now. But it's hard for journalists to get inside. Some comments said that's the reason why people doubt the seriousness of the situation. You were quoted in that article saying that "journalists can convey stories in a way that doctors and nurses just can't always manage." Could you elaborate on that? Do you still feel the same way?

Morton: I'm conflicted in some ways. I feel journalists are important, especially at this time and in vulnerable areas. But at the same time, there's a big safety issue. They also quoted me when I said that it's not war photography, where you're just taking responsibility for yourself. This time, it's an infectious disease. You're just not taking responsibility for yourself. You're taking responsibility for everything, everybody around you, every time you take an assignment, every time you go out there. So it's a risk assessment on a case-by-case basis.

When I think about assignments, I think about what I'm adding to this story. What's the general conversation? Am I adding something new? If I'm not offering anything new, is it worth my safety? Is it worth the risk? How passionate am I about the story right now, and is it worth telling?

I have mixed feelings now with people embedding themselves in hospitals. I think it's important, but at the same time, health care providers don't have PPE. And those PPE should be allocated properly. So what are you adding to the story by embedding yourself that's going to be unique, that you need to take away those PPE from those people?

Da Silva: What kind of an impact are you hoping that this work will have, specifically your healthcare hero portraits?

Morton: With all of my COVID-19 work, I ultimately hope that it resonates with people how important it is to stay safe, keep social distancing, keep wearing masks and maintain hand hygiene. I know that since we're all isolated from each other, it feels like it's not real unless you physically see it. But it's happening, and a lot of people are dying. We just have to keep sharing how important it is to take it seriously.

Da Silva: What are the ethical concerns around photographing any infectious disease or patients? What are the things that you think about?

Morton: One of the biggest things for any health stories are the HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) regulations. Health information privacy is super important, so you have to get the consent of the patient. With really sick COVID-19 patients, they're not consenting for themselves—sometimes their families are consenting for them. If you're in this acute phase in the hospital, you won't necessarily have the time to ask for permission. It's really tricky.

Sometimes I wonder how people are able to work that in. The work I've done within the hospital, there are no patients so the hospital looks empty. But it's definitely not empty. I've just found other themes, because HIPAA laws are very difficult to work around.

To watch Rosem Morton's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB member. As a member, you'll have access to all of our "Storytelling for Change" sessions that feature notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Originally from rural Alaska, Cari Payer grew up seeing the outside world through the lenses of National Geographic photographers. The images inspired her to see what the world had to offer beyond her small community. This passion started her journey around the globe to photograph people, landscapes and cultural landmarks in America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

Cari first became involved with Photographers Without Borders by attending Storytelling School in Mongolia. She later spent time in Nepal in 2018 capturing what she calls “small vignettes of life." During the spring 2020 lockdown in Tokyo, Cari created a photo series featuring her daughter titled “COVID-19 Spring Collection 2020.”

Cari was in conversation with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion which touched on teaching photography workshops, empowering stay at home spouses and small home business owners to use photography more effectively in their lives, finding opportunities during COVID-19, ethical travel photography, how to capture unique moments and the importance of sharing knowledge in the world of photography.

Danielle Da Silva: You grew up in rural Alaska and have lived and travelled in a lot of different places around the world. How does your personal experience come into your storytelling and love of teaching?

Cari Payer: I love being an educator. I gravitate towards that even more than being a full-time photographer because I like helping people realize their ideas. Just because we go to tourist destinations doesn't mean tourist destinations are what we need to photograph. It's important to get a little deeper and learn about the culture and interact with people. We're not just there to take pictures of people who don't look like us and move on. We're there to experience and be part of their life and to help lift their voices or educate our own. We can then bring that information back and help spread it so everybody can feel heard in the world.

Images by Cari Payer

Da Silva: How did you end up teaching workshops?

Payer: My husband works in multiple locations, so we've been lucky enough to spend time in Hawaii, Germany, Florida and Tokyo. But the flip side of that is I can't establish anything for very long since our average time in a location is 18 months.

I've been a food photographer and worked a lot of commercial jobs, but there were times when I reached out to other photographers who inspired me for help and was brushed aside. Frequently in the photography industry, there's an idea that the work is a secret. For example, if you Google how to do something in photography, the first blog post is “Top Five Secrets On How to Take Landscape Photos.” Here's what it says: stand in front of a landscape, click the button, and you've taken a landscape photo. It's not really a secret. I'm not saying it doesn't take a lot of practice and technique. But this idea that how to take photos is a secret—it drives me crazy. And that's the reason I spun into teaching workshops.

Image by Cari Payer

Da Silva: What do you like best about teaching people who are new to photography?

Payer: I love helping people achieve whatever they're trying to communicate. We sometimes don't have the tools or skills yet, but that doesn't mean we don't have the story, ideas or creativity. In the photography industry, it's hard to find people who are willing to genuinely help you figure something out.

Sharing knowledge is crucial. One time, a student wanted to do a cool portrait shoot, and I'd never done anything like that. So I said, "Let's sit down and use the knowledge I have and the idea you have and try and come together and work it out." Having that human connection is one of the joys of teaching.

Image by Cari Payer

To watch Cari Payer's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Johnny Pham (c) Johnny Pham Photography

Brooke Shaden is a conceptual fine art photographer specializing in self-portraiture that revolves around rebirth, death, beauty and decay. While exploring the light and darkness in people, she has received awards for her cohesion and storytelling abilities. Beyond self-portraiture work, Brooke is a dedicated philanthropist who teaches self-expression workshops for survivors of human trafficking. She also founded The Light Space, a photography school for survivors in India and Thailand.

As part of Photographers Without Borders (PWB) ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series, Brooke joined PWB Founder Danielle Da Silva for a conversation on creativity.

Below are edited excerpts from the discussion, which touch on Brooke’s unique self-portrait style of photography, her creative process and inspiration, creating art in the midst of quarantine, the power of storytelling and how to create a self-sustaining business.

Danielle Da Silva: How do you approach storytelling? What makes a good story, and how do you find them?

Brooke Shaden: This is the topic I'm most passionate about. To me, the best storytelling comes from taking something you feel strongly about on a personal level and opening it up to a wide audience. I know a lot of artists are of the opposite opinion and say if you're a real artist, you don't create for anybody but yourself. I agree that it's always best to create because you feel called to do that. But 50 percent of the reason why I make art is to share it with people. I look for that connection. The best stories are the ones you feel called to create because you just have to make it. But where you can also equally think about how it might touch other people.

The way I do that is through symbolism, finding universal languages everyone around the world can connect to and use to understand the story. In my images, I try to create this sense of universal symbolism where the locations, the props, the wardrobe, things that I'm using, have some resonance to anybody in any culture. Maybe I'll use a clock to represent time. I keep it really simple so my imagery isn't overwhelming but atmospheric enough to resonate with the widest audiences.

Images by Brooke Shaden

Da Silva: In this world, every action has a reaction. What reaction are you trying to get? What change are you trying to make?

Shaden: I'm trying to promote introspection. The most good comes out of people when they confront themselves first, so they can confront the world after. But we often do the opposite. People's natural reaction is to be social, to put themselves out there, to react to the world and then come back to themselves.

When you have a midlife crisis or when something isn't in alignment, I really want to encourage people to start with yourself first. You'll only be able to truly touch the world once you've connected to yourself first and foremost.

Image by Brooke Shaden

To watch Brooke Shaden's entire webinar, join our community by becoming a PWB community member. As a member, you'll have access to all "Storytelling for Change" sessions featuring notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Wildlife conservation advocate and National Geographic photographer Ami Vitale has traveled to more than 100 countries, bearing witness not only to violence and conflict but also to the surreal beauty of nature and the enduring power of the human spirit. With over 1.2 million followers on Instagram, she uses her platform to inspire people to protect nature and see their interconnectedness to each other and the world around them.

Ami joined Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion, which share Ami's thoughts on staying sane during COVID-19, protecting nature, finding your purpose and practicing gratitude.

Danielle Da Silva: How are you keeping healthy and sane? How has your day-to-day been affected by COVID-19 and everything that's happening?

Ami Vitale: It's the first time in decades that I've spent so much time at home. The last two years, I’ve spent a maximum of three weeks at home. I was always on the road. The funny part is, every single night I've been having dreams that involve planes, missing taxis or missing a connection. But last night, I had my first dream about a Zoom video call.

I'm really trying to use this moment to reimagine my own impact and future in a way that doesn't involve as much travel. Personally, the big takeaway is that nature is sending us a really strong message. And instead of wrapping our minds around the anxiety of the unknown, this is such a great opportunity for all of us to reinvent ourselves, reimagine, be optimistic about how we can create the life we truly want to be living. It's a great moment to breathe.

Image by Ami Vitale

Da Silva: What do you feel your purpose is?

Ami Vitale: I want to lift people up wherever I can. Negative thoughts are toxic and contagious—they can drag us all down. But we can all lift each other up through attitude and how we view things. I've been fortunate to see many different perspectives and to look at this world from many different angles.

Sometimes, the story or purpose is literally right behind you. But your camera is pressed up against your face, giving you tunnel vision. We all get obsessed with that one thing in front of us, and we forget to turn around, take the camera down, view it from another angle, and see how different the world looks.

Image by Ami Vitale

Da Silva: Of all of the teachings you've ever received, from all of your travel to more than 100 countries, what is the most profound teaching you can share?

Ami Vitale: It's a tough time, and it’s okay to honor that. I've had days where I'm filled with despair, and I just don't feel I can get out of bed. The way I've gotten out of that was to sit and think about all the people I’m grateful for and write thank you letters to them. And a few hours in, I began to realize everything wasn’t so bad.

A good night's sleep also helps. I’ve had trouble sleeping during the pandemic, but sleep helps—and so does getting out into nature. I saw Iceland did a tree hugging campaign, and I thought, “Yes, do it! Literally do that.” If you're feeling lonely, go hug a tree. Also, know that everything is temporary in life. That awful feeling will pass and helping other people or creatures makes everything feel better. So go out and explore and document your world—photography is a great escape for anyone.

You can watch Ami Vitale's entire webinar by becoming a PWB Member. As a member, you’ll have full access to all online “Storytelling for Change” webinars that feature notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Image by Ben Sturgulewski

Driven by a passion to capture the unique perspectives not yet thought of, Krystle Wright is a pioneering photographer and director from Australia who's accelerating awareness of the world's most extreme sports and athletes. On a continual quest to challenge herself mentally and physically, Krystle consistently brings attention to the demanding adventures and landscapes the public is rarely exposed to.

Krystle's assignments have covered all seven continents in over 55 countries—from the Australian outback to the Antarctic. Her images have been published in National Geographic magazine, Outside magazine, The Times, GQ, Red Bulletin, and the Huffington Post. She's also a regular contributor to the @NatGeoTravel Instagram account.

To share her latest adventures and lessons learned, Krystle joined Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion, which touched on Krystle’s experiences storm chasing, her journey from sports photographer to adventure photographer, career advice for aspiring freelancers, how to kit-out your vehicle for adventure photography and what home means during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Danielle Da Silva: You have a tagline “curiosity over common sense”. What does that mean to you? And how did that come to be a thing?

Krystle Wright: I never said that until I did a project with Garmin where I went to Norway to free dive with orcas. Someone on their team made me a little patch with a hand-sewn orca and message that said “Curiosity over common sense”. It's one of my most favourite gifts. But when it comes to curiosity over common sense, it doesn't mean you can just be a moron and be excused for it. It's having a curious sense of the world around you without trying to overthink and reason everything. Gosh, if we try and reason everything we do, nothing makes sense. We have to let curiosity drive our photography because if we overthink, then we hold ourselves back.

Images by Krystle Wright

Da Silva: What are some realizations you've had during COVID19 regarding travel and otherwise?

Wright: When that pandemic hit, I know all of us have been on an emotional roller coaster whether we’ve wanted to or not. I was a freelancer—and I feel like most photographers these days are freelancers. It's tough because we're always taught to say yes to everything. You can say no later, but you never do. You say yes to everything, and you take on too much.

The fear is, "Where's my next job coming? How am I going to pay the bills? How am I going to live?" Freelancers have the drive to work, to create, to be relevant. Personally, I was caught up in a cycle, and I didn't know how to stop it. Last year was one of my worst traveling years, because I was almost changing time zones every bloody week. It's almost like I needed the pandemic to actually reset.

I've come to realize that I definitely don't need to travel as much. For the first time since 2007, I finally got to be home for the first winter change on the Sunshine Coast in Australia. I've always come home and appreciated it, but I'd forgotten the little things.

Images by Krystle Wright

Da Silva: What’s your advice for freelancers?

Wright: All I can say is don't sell yourself short. When I started my career, I did shifts for free because it was work experience. You know when it feels right and when there's going to be return from putting yourself out there. And then you know when companies are being downright cheap to use you and your social media and your skill set as a photographer. But you deserve more. You deserve to be paid.

I keep going back to social media because it has replaced a lot of traditional marketing, but companies still have a budget for marketing. They should be paying for your work. It’s so easy to go, "Oh, I love your idea! I'll do whatever it takes to make it work." But at the end of it, you don't get paid. When you really stand your ground and tell what you're worth, stick to it. People will have more respect for you. But I know it's tough to fight for what you're worth.

Images by Krystle Wright

Images by Krystle Wright

Images by Krystle Wright

Images by Krystle Wright

Images by Krystle Wright

Images by Krystle Wright

You can watch Krystle's entire webinar by becoming a PWB Member. As a Member, you'll have full access to all Storytelling for Change webinars that feature notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

While struggling with anxiety and depression as a teen, Bryce Evans picked up a camera to document his feelings. Now an award-winning photographer, Tedx speaker and the founder of The One Project, he shares how photography can be used as a therapeutic medium to heal past traumas and maintain positive mental health.

Bryce sat down with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) founder Danielle Da Silva for a candid conversation, which dove into his personal struggles with loneliness, the benefits of therapeutic photography, becoming your authentic self and healing through community.

Below are edited excerpts from the discussion—just one of many in PWB's ongoing Storytelling for Change webinar series.

Da Silva: I've been excited for this session, not only because I've heard so many good things about you from other people, but also because I admire the work you're doing. I strongly believe in photography as a therapeutic tool. Can you share a little about yourself and The One Project?

Evans: The One Project is a social enterprise that evolved out of my first series of photos. It was a way of talking about my mental health for the first time. I went through a lot of depression and anxiety as a teenager, but I didn't really know what was happening at the time. Through my photos, I created stories focused around loneliness. And I saw how no one was talking about how photos could be used to express this feeling.

One photo I took has a second person in it, but I only noticed them a year or two after creating the series and sharing with others. You have your intention and your perspective with your photos, but by sharing them, you spark insights in other people. Having conversations can change how you see it and how you feel about it. Going through that process years later and working on myself, I understood that I had people in my life who were there for me—friends and family. But at the time, I wasn't able to see the support. I almost intentionally created loneliness in my photos and in my life.

Images by Bryce Evans

Da Silva: We share so many of the same struggles and often don't talk about them, which is the biggest power behind what you're doing. You're creating a community of people who can talk. I think a lot of folks are hesitant to delve into work like this because they feel they're not professionally qualified. What's your background?

Evans: My background is in marketing. I'm mostly self-taught in everything artistically, so a lot of what I do is learning on my own. But there are struggles. There's confusion about this type of work and the terms being used. We call it therapeutic photography, and that's the main term if you're not a professional or working with a therapist. We use many of the same techniques as phototherapy, which is done with a registered therapist. It can be a challenge, but having the right places to direct people if they're in crisis or if they do need professional help is one of the most important pieces.

Images by Bryce Evans

Da Silva: There's a lot of strength in the fact that you're not a mental health professional. And the idea of building an online private mental health community is interesting because it allows the community to build it into whatever it needs to be to support one another. But in creating a community like that, what protocols have you taken to ensure it's a safe space?

Evans: Yes, we have a private community. It's not indexed by Google, so you have to log in and become a member to access any of it. We do share a lot of stories publicly, but we have different sequences in place for people to give permission. Anytime we share something on our website or social media, we've gotten express permission from those members. A lot of people share stories, sometimes for the first time, so it needs to be a safe and supportive space.

Da Silva: There's a great quote I came across by Howard W. Thurman. He says, "Don't ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive." I think your struggles can become your superpowers and help you realize a part of yourself that you may not have even known before. Just generally what are your reactions to that?

Evans: I got shivers, which is always a good sign. That’s it perfectly. I've seen very clearly myself with this project. And I've seen how other mental health advocates have become stronger and more educated about mental health issues through their lived experience. They have a lot of value to share with the world.

Images by Bryce Evans

Images by Bryce Evans

Images by Bryce Evans

Images by Bryce Evans

Images by Bryce Evans

You can watch Bryce's full interview, and the entire Storytelling for Change series, by becoming a PWB Member. You'll have full access to the series, which features notable photographer storytellers from around the world. To join our upcoming sessions, register here.

Image by Anna Heupel

Cristina Mittermeier is one of the most influential conservation photographers in the world, but her first love didn't involve a camera. Cristina's passion for the natural world, both above and below the surface, began in childhood and led to her career as a marine biologist, working in the Gulf of California and the Yucatan Peninsula in her native Mexico.

After realizing the power of photography to spark interest in conservation, Cristina picked up a camera to share stories from the farthest corners of the Earth. Today, she's a National Geographic contributing photographer, a Sony Artisan of Imagery, and the Co-Founder and Managing Director of the ocean conservation non-profit Sea Legacy. Known for her sensory storytelling, Cristina is the first female photographer to reach one million followers on Instagram and the editor of over 25 coffee table books on conservation issues.

Cristina sat down with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of the ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from the discussion, which dove into the secrets of impactful storytelling, indigenous wisdom, biodiversity, lessons of the global pandemic and following your passions.

Danielle Da Silva: Cristina, you're one of the biggest change-makers I know. No problem seems too big for you. How do you find the energy to tackle these problems?

Cristina Mittermeier: I share a network of friends and acquaintances that I've made throughout the years – people like you. Paying attention to the people around us is really important. But when I work with passionate people, it fills me with energy. I can't wait to get up in the morning and get out there.

I’m also a mom with three kids, and I think about the planet we live in today. Yesterday, I looked out the window and saw a gray whale feeding right out my window. I would love for my children to know there are going to be whales when they're older. That we're going to not have to worry about an apocalyptic future. So that's where I get my energy from – there's no choice.

Images by Cristina Mittermeier

Da Silva: What's most extraordinary about you is that you're always at the leading edge of stories pushing for change. Can you tell us about what makes a good story for you and why storytelling is so important?

Mittermeier: We are all born with the ability to tell stories. Somehow when we're young and are required to sit still and memorize mathematical tables, storytelling is forced out of us. So we have to remember how to tell stories. Some people get lost in the details, but those don't matter. The big themes in our lives are what matter. And if you're able to pay attention and pull from a lot of sources to make a story relevant, you're going to tell an interesting story.

Personally, I practice storytelling. You'll see me talking to myself in the car and telling stories to my neighbours, my mother-in-law and my children just to see what resonates. Usually, it's authenticity – to have a bigger purpose than simply entertaining – and being passionate. That means being fearless and not being embarrassed to care about the things you care about.

Images by Cristina Mittermeier

Da Silva: Do you have any advice for people who have a small audience and are trying to make an impact?

Mittermeier: Every follower is amazing to have. When I give a lecture for 1,000 people in an auditorium, I feel lucky and happy if one person says to me at the end, "You've changed my life." If the other 999 were just entertained, that's okay. If you can change five people in your audience at a time, that's great. Because they're going to go and change another five. So the size of your audience doesn't matter. What matters is the depth of your messages.

Images by Cristina Mittermeier

Da Silva: Right now we are in the midst of a crazy crisis. What are your thoughts around what's going on around COVID-19?

Mittermeier: The thing about COVID-19 that really struck me, because it's not the first time a virus has jumped from a wild creature to humans, is that it didn't happen sooner. HIV gave a good try. Ebola had a foothold. But it took COVID-19 to shift the world.

I was married for 20 some years to a primatologist who recently wrote a paper called the Coronaviruses and the Human Meat Market. It recognizes that complex animals like humans take a long time to adapt and evolve. But microbes, viruses and bacteria are quick. They mutate and adapt all the time. When you bring them into a market and give them the opportunity to jump from a wild animal, where they have been self-quarantined out in the jungle somewhere, to a domesticated animal and then a human, things get messy quickly. And that's exactly how COVID-19 started.

Da Silva: We were having a conversation recently, and you said we need to put nature in quarantine. Can you share what you meant by that?

Mittermeier: There are billions of humans on this planet, and we have forgotten the integrity of the fabric of life that gives resilience to the entire system. The only reason the ocean produces oxygen is because it's alive. But when we keep dumping sewage and pesticides and fossil fuels into the ocean or taking fish out, we're undermining the resilience of the system.

COVID-19 is horrible, but thank goodness this is not the worst virus that could have hit. If we want to prevent the next pandemic, we need to make sure we're protecting at least half of nature on this planet. That means creating more national parks and monitoring marine protected areas. But the first order of business is to ban wildlife markets. If you're ready to help, sign the declaration asking governments around the world to ban wildlife markets. It's time.

To learn more about Cristina, explore her work or follow along with her adventures on Instagram @mitty. You can watch her entire webinar by becoming a PWB Member. As a Member, you'll have full access to all Storytelling for Change webinars that feature notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Photo by Matilde Simas

Sophie Otiende is a feminist teacher, a survivor advocate for human trafficking and the first Kenyan to receive the Trafficking in Persons Report Hero award. For the past five years, she has been working with HAART Kenya, a Photographers Without Borders (PWB) partner organization that's dedicated to supporting survivors of human trafficking and raising awareness in order to eradicate this criminal activity.

Sophie was recently in conversation with PWB Founder Danielle Da Silva, where she shared the power of stories to create change, educate and empower. (You can watch the video highlight here). Below are edited excerpts from their discussion, which touched on the complex system of human trafficking, feminism in the African context, historical impacts of colonialism, capitalism and racism, and the power of storytelling to shape narratives and address injustices.

Danielle Da Silva: Can you enlighten us a little bit more on what constitutes is human trafficking and where it exists?

Sophie Otiende: Human trafficking is everywhere. The legal definition is very, very long, and it's different for an adult than for a child. Basically, for trafficking to occur, you have to find what we call the act – the means and the purpose. How did the person enter the situation? The means is how a person is controlled if they're an adult. And then the purpose is always for exploitation.

So if I'm targeting someone, I'm finding a way to control them. That could be through deception, kidnapping, coercion or grooming – and then I'm exploiting them. The exploitation can be labour, can be sex, can be for an organ, can be for different purposes.

A simplified definition is the sale of people for the purpose of exploitation. Literally, human trafficking is a business because, at the end of the day, it's a system that runs on profit.

Photo by Matilde Simas

Da Silva: It’s the second-largest illegal trade in the world. So how does that happen? How do you relate human trafficking to capitalism? And even colonialism and white supremacy?

Otiende: It's the whole concept of demand. We have the West constantly consuming and demanding food, so you're going to need people working in fields for long hours. In the past, families could produce food that was enough for villages to work, to eat, and to spend.

But now, all of us want strawberries. When it's not the season for it, someone has to pay a price for that demand. So we have to start questioning our lifestyle and whether all these things are worth it in the end because someone who doesn't have as much power or privilege as you is the one who's paying the price.

I mean the foundation of the world is white supremacy. So of course, it's the most vulnerable people, it's the darkest people who are going to pay the price. The majority of the people who are trafficked for forced labour, for anything, are black women and girls.

Photo by Matilde Simas

Da Silva: Can you tell us about the power of storytelling for good? How can we use that in a good way to support survivors or communities that are in need?

Otiende: Right now, most stories have been written by people who come in with a lot of privilege. We all come into every story with our bias, and it's extremely important to actually question that.

First of all, you have to identify the power that stories hold – to identify that as a storyteller, you have power. You have the ability to destroy and to build someone, and to open eyes. And it's easy for you to abuse it. So how do you hold yourself accountable for that power? And how do we create a system that actually wants you to be accountable?

Secondly, recognize that a story doesn't belong to you just because you're managing the tools for storytelling. So long as other people are involved, the story isn't yours. Storytelling is a collaborative process between you and the people who you're walking with, especially when you're working with survivors. Above all, it’s theirs.

Da Silva: What is the greatest teaching you have ever received?

Otiende: For me, the most important teaching that I've learned is from Audre Lorde. And it's the simple statement that the personal is political. There's nothing, absolutely nothing, I do as an individual that's not political. I'm responsible for the power that I have, and I'm responsible for how my power as an individual affects and builds a narrative.

I believe that my personal life is the first political statement. So the only way I'm going to change anything is by not being hypocritical and applying the very things I'm saying into my own life. When I say that people need to be empowered, it's not to be preachy. Let's not be people who are preaching to others and not doing it ourselves.

To watch Sophie’s entire interview, including a viewer question period, please consider becoming a PWB Member. As a Member, you'll be contributing to PWB’s social action initiatives and have full access to all Storytelling for Change webinars that feature notable photographer storytellers from around the world.

Michelle 'Shel' Scott is an occupational therapist, storyteller and producer. In her work with clients, she blends therapeutic approaches, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, dialectical behavioural therapy and exposure theory, with other approaches like meditation and mindfulness. Shel explores the intersection of mental health therapy and activism, higher states of consciousness, and indigenous and ecological worldviews. She aims to come to a deeper understanding of all these topics and viewpoints in order to promote greater well-being among individuals, communities and the world at large.

Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva recently chatted with Shel as part of PWB’s ongoing “Storytelling for Change” webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from their discussion which touched on facing mental health challenges during the pandemic, the importance of mindfulness, building community, forest therapy and indigenous ecological knowledge.

Danielle Da Silva: What’s your advice to activists for maintaining balance in their mental health when they feel overwhelmed by the big problems they're facing?

Shel Scott: Burnout is very real and very high in the social justice sphere. Taking breaks, taking time off the internet and stepping away is really important. It's good to find other people who can validate and support you, and who you can support as well, so you don't feel like you're alone.

It's super overwhelming to think about a huge goal like, 'Oh, all we have to do is take down capitalism.' Instead, think about one actionable thing that's happening in your society. And rather than trying to start your own thing, look at what other people are doing for whatever issue speaks to you most – whether it’s wealth inequality or food security. There are probably some initiatives that have already been started. Then, take action on that one thing.

I know it's hard to pick one thing. But there are a lot of movements that have gotten traction and involvement in recent years where people are using the slogans, sharing the logos and meeting in the streets. A lot of that is very well-intentioned, but they don't have an ask or a small list of demands that they're coming down on. So that momentum hits the wall and dissipates rather than being a pressure point.

Instead of thinking about taking on the monolithic beast of capitalism or colonialism, for example, find one group or committee in your area that's doing something that you believe is important. Concentrate on that one thing, and change will feel more possible.

Photos by Shel Scott

Da Silva: Do you have any thoughts about accessible ways that people can nurture themselves during the pandemic?

Scott: Now that we're all relegated to the digital sphere, I recommend having conversations where you might agree not to talk about the pandemic. It's good to take a break from that. Remember, you are allowed to have time outside of that to kind of collect your thoughts. For example, forest therapy is a free way to nurture ourselves. So much psychological scientific evidence shows that just being around trees makes people feel safer, more at ease and less anxious — it really brings physical markers of stress down. Communing with the natural world is where the scientific and the spiritual intersect.

Photos by Shel Scott

Photos by Shel Scott

Photos by Shel Scott

Photos by Shel Scott

Photos by Shel Scott

I live in a big city, but a couple of days ago, I went for a walk and just noticed all of the beautiful flowers. I spent time gazing into them and contemplating them and offering gratitude for them. It completely brightened my day. If you can’t get outside for whatever reason, simply having plants in your home provides similar benefits to forest therapy.

Of course, we can't talk about the value of communing with the natural world for therapy without talking about indigenous knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge. This worldview has been available to us for millennia, and it's a different way of being in and relating to the world. I'm not the best to speak to this because I'm not indigenous myself, but I imagine it to be the difference between being colorblind and then being able to see color. It's something that you can't actually describe. But the lessons are there, and the teachers are all around us.

To learn more about Shel’s work, visit her website, and follow her blog Running Around Being Passionate.

You can watch Shel's full interview, and the entire Storytelling for Change series, by becoming a PWB Member. To join our upcoming sessions, register here.

Benjamin Von Wong's work lies at the intersection of fantasy and photography by merging everyday objects with fantastical subjects and shocking statistics. It's attracted the attention of corporations like Starbucks, Delve, and Nike and has generated over 100 million views. Yes, he's gone viral for causes like electronic waste, ocean plastics and fashion pollution—which is why he's been named one of Adweek's 11 branded content masterminds.

Recently, Benjamin was in conversation with Photographers Without Borders (PWB) Founder Danielle Da Silva as part of PWB’s ongoing "Storytelling for Change" webinar series. Below are edited excerpts from their discussion, which touched on Benjamin’s inspiration, creative process, activism and desire to build communities over audiences.

Danielle Da Silva: Can you tell us a bit about your career path and how you've found yourself where you are right now?

Benjamin Von Wong: As I started climbing the ranks of photography, I always dreamed of doing commercial work. But I soon realized that earning money doing something I enjoyed wasn't enough—I was looking for more meaning, more drive, more purpose. Because once you get a big campaign, where do you go from there? You just line yourself up for the next campaign; there's no human development in it.

I almost quit photography at that time, and I went into documentary filmmaking. I started making stories for charities and thought I could have a path creating fundraising videos. But I didn't enjoy it that much, and I wasn't that good at it. So I started wondering, "How might I tie fantasy and impact together? How do I take these two worlds that are really different and smash them together?"

That was a journey, which started off with projects like tying a model underwater and adding a shark in to support shark conservation. Or taking a mermaid, which is in the fantasy world, and finding 10,000 plastic bottles to put her on to raise awareness for plastic pollution. I found different ways to combine causes and fantasy together. Over time, those combinations have become larger and more complex.

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Da Silva: I know you've had experience with building community and making a tangible impact versus building an audience. So can you tell us the difference? And why one matters more than the other for you now?

Von Wong: I have about half a million followers on social media that I've built up over a couple of years. What I've realized is that my followers are just waiting for me to create things so that they can consume it, right? They're just waiting for me.

If you're building an audience, you fall under the constraints of having a content schedule to entertain people so they can consume, consume, consume. But they're never going to be satiated and are always going to want the next thing. As a creator, it gets quite draining, especially when you need to constantly ask the questions of why are we creating, what drives me, what am I inspired by?

A community, on the other hand, is different. It thrives on its own and doesn't necessarily depend on any one member to function. People in a community rally together to co-create, to co-inspire, to share discoveries and learnings. There's a sense of shared transformation. If you design a community, the hope is that these one-way conversations thrive into multi pronged conversations—that's when you actually grow.

It's a little like when you go to a conference and hear a person speak. You get inspiration, but it's the connections you make at the conference that drive the lasting change over time. The connections are where you get your resilience and sustainability for your own creative process.

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Photos by Benjamin Von Wong

Da Silva: You talked about how your process has shifted. Now, instead of thinking about the grand outcome, what are you trying to affect first?

Von Wong: Every project starts with, why are you doing this? You're not just trying to create content for the sake of creating content. What are you trying to achieve? And asking the right questions, in the beginning, is super important and helpful.

Keep in mind, just because someone went viral once doesn't mean they can go viral again. It also depends on when they went viral. Because what it took to go viral in 2014 is very different than what it took to go viral in 2016, which is super different than today. You might become a genius at Instagram, but then Instagram changes the algorithm. Then what? All those principles you thought you knew no longer are valid, and that's completely out of your control.

That being said, creating good art and stories that resonate can still be timeless in a sense. You just have to adapt them to the medium on which you're going to create.

To learn more about Benjamin's work, follow him on Instagram, listen to his podcast "Impact Everywhere" or view prints on his website.

You can watch Benjamin’s entire interview, including a viewer question period, by becoming a PWB Member. As a Member, you'll be contributing to PWB’s social action initiatives and have full access to dozens of Storytelling for Change webinars with notable photographer storytellers.

Daniel Berehulak is an award-winning photojournalist who has found himself on the front lines of crises all over the world. His work focuses on a combination of breaking news, human rights and social and health issues reporting. He's visited over 60 countries covering history-shaping events, including the Iraq War, the trial of Saddam Hussein, child labor in India, Afghanistan elections and the return of Benazir Bhutto to Pakistan, and documented people coping with the aftermath of the Japan tsunami and the Chernobyl disaster.

His work has been recognized with two Pulitzer Prizes. In 2015 for feature photography for his coverage of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and in 2017 for his breaking news photography, covering the so-called war on drugs in the Philippines – both for the New York Times. In 2011 he was also a Pulitzer finalist for his coverage of the 2010 floods in Pakistan. His work has also garnered six World Press Photo awards, and two Photographer of the Year awards from Picture of the Year International. Originally from Australia, Daniel is currently living in Mexico City where he is covering the COVID-19 pandemic for the New York Times.

Berehulak recently was in conversation with Danielle Da Silva – the Founder of Photographers Without Borders (PWB) – to discuss integrity and ethics in storytelling and vital considerations for covering COVID-19 in Mexico, which along with countries in South and Latin America is the newest epicenter of the devastating pandemic.

Photos by Daniel Berehulak

Danielle Da Silva: In your reporting, you are conscious of not reducing the people you follow and photograph for a story as “subjects”. You talk about them as collaborators. Why is that?

Daniel Berehulak: I think it's quite degrading when we call people subjects. People have a name. …They're collaborators and are happy to sit down and for us to interview them. We’re there to learn more about them. And in that way, they're absolutely collaborators in telling the story. In some ways, we’re just a conduit of that information. That's why as photojournalists, I feel it's more important to be better journalists than photographers. It's important to share people’s names and identities so we can actually connect with them.

But we need to be able to have the context of what is happening in this situation. We have to ask, why is this photograph important? That's something I always try to keep in the back of my mind when I'm working on a story. I'm always thinking about the story and the best way to pull in all of the elements, the way to document it, to illustrate it. And that comes with being a good journalist. You know, hanging around longer than anyone else, interviewing people, fact checking, double-checking information, cross-checking information. When we do that, we realize the importance of what is happening in front of us.

Da Silva: How do you feel about being an ethical gatekeeper? You could choose not to submit certain images, like let's say to New York Times, or wherever you're working. How do you go about managing that responsibility?

Berehulak: Managing that comes from an integrity that you need to have with your work and from knowing that the images you are filing are the truest form of your understanding of the truth that there is. Because there have been a number of times when an image gets filed and is taken out of context – you see it in press conferences when a politician goes to like scratch their eye and it appears that they're crying or anything like that.

I've had images where someone appears to be reacting in a way, but I know it's not a true representation, so I won’t file it. I'll keep on shooting until I'm able to capture something that is illustrative of the story or the person I'm covering. We have to be the ethical gatekeepers of the work we present. It's a very fragile thing because we're responsible for the information that comes out. So we have to be extra careful with it and double check information to ensure it is of the highest integrity.

Da Silva: For you, what makes a great story? How do you find your stories?